During the Great Depression, countries discovered their balance sheets. Fiscal spending helped augment aggregate demand. After the WWII, high income countries have typically run persistent deficits, resulting in the accumulation of debt.

During the Great Financial Crisis, central bank balance sheets were discovered. Central banks bought a variety of assets, but especially their own government bonds. The idea was that the proximity of the zero bound (zero policy rate) could be overcome through the purchases of bonds and the expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet.

Some economists have argued that the bond buying by the Federal Reserve lowered the 10-year yield by as much as 85 bp. We are skeptical. The Fed did not simply buy long-term securities. It is better to understand the asset purchases as an asset swap. The Fed swapped reserves for the bonds. It took duration out of the market, for sure, but this is not the same thing as getting beyond the zero bound. Moreover, reducing the term premium of bonds is not the same as cutting the Fed funds rate.

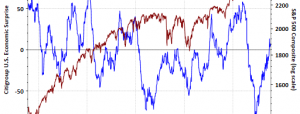

This is important because the Fed has begun allowing its balance sheet to shrink, and some argue that this is tantamount to tightening of policy. Indeed, Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca at the Council on Foreign Relations warned that the Fed’s balance sheet reduction that has been announced is tantamount to a 100 bp hike in the Fed funds rate by the end of next year.

Steil and Rocca’s concern is that the markets and the Fed do not seem to be aware of this. They note that neither the Fed’s forecasts (dot plot) nor the Fed funds futures strip through 2019 have reflected the impact of the balance sheet reduction. They conclude: “These facts suggest that they [Fed and investors] are largely ignoring-and therefore the greatly underestimating-the tightening impact of the balance-sheet reduction.”