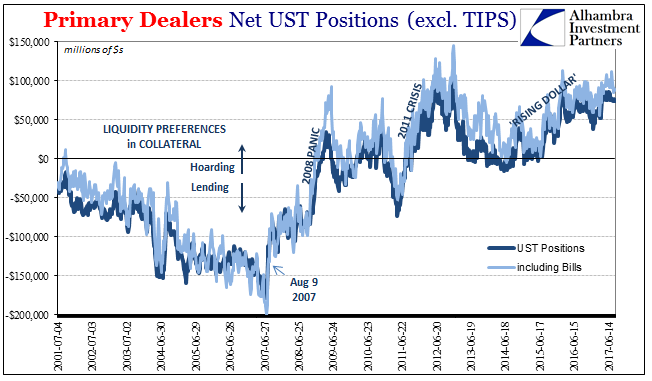

The Federal Reserve Bank of NY reported on Friday that repo fails for the week of September 20 were $359 billion (combined “to receive” plus “to deliver”). That’s the second highest weekly total of this year, following $435 billion fails recorded just two weeks earlier. The week in between those two was also high, tallying $325 billion.

That makes for three consecutive weeks of unusually high repo fails. While most of the repo market operates in hidden spaces without much notice, one thing we can always depend upon is the correlation of repo fails with collateral problems.

The occasional jump in fails had always plagued the repo market to some degree. A “fail” is pretty simple and straightforward; when the obligation of any seller to deliver agreed upon securities remains open following the close of business on the agreed date of the transaction. These are, after all, repurchase agreements, which means exactly what the name implies; I buy bonds from you today and agree to sell them back tomorrow (or whenever). If I don’t sell them back to you tomorrow, we have a fail.

The reason for them relates to what repurchase agreements actually are; collateralized short-term loans, mostly overnight. They are structured as repurchases for historical reasons that since the 1980’s have been superseded by this reality.

Despite the implementation of a “dynamic fails charge” in May 2009, fails have been occurring in UST’s especially the last three years with growing frequency. In a world of collateralized funding, as weird as it sounds there are times when that collateral is more dear or valuable than cash. Rehypothecation is one reason for that, as is the structure of securities lending more broadly.

In 2008, this relationship was very easily established; T-bill rates in particular would trade in equivalent yield far less than they otherwise “should” given money substitutes (such as the IOER). Bill rates fell sharply in the wake of Lehman’s insolvency, and repo fails exploded into what is now the textbook (well, one not written by an Economist, anyway) case.